1895 ROGERS TYPOGRAPH

By the mid-nineteenth century, inventors were devising new ways to making typesetting more efficient. The printing press had evolved considerably during the Industrial Revolution, but typesetting had been stagnant since Gutenberg came up with the idea 400 years before. Print shops were still setting type by hand, pulling out one letter at a time to compose whole pages of text. This was a very slow and arduous process, so printers were eager to come up with a better way. One solution was to have a machine set type for you, but this proved to be very complicated. The idea that took off instead was the typecasting machine. Rather than using existing type and putting lines of type together letter by letter, a typecasting machine would create new letters to form whole words and sentences.

The Linotype was the most successful machine to capitalize on this idea but there was actually a second machine that approached the idea of type casting in a slightly different way. This other machine was called the Rogers Typograph. It was created by John R. Rogers who was a schoolteacher by day and an inventor by night.

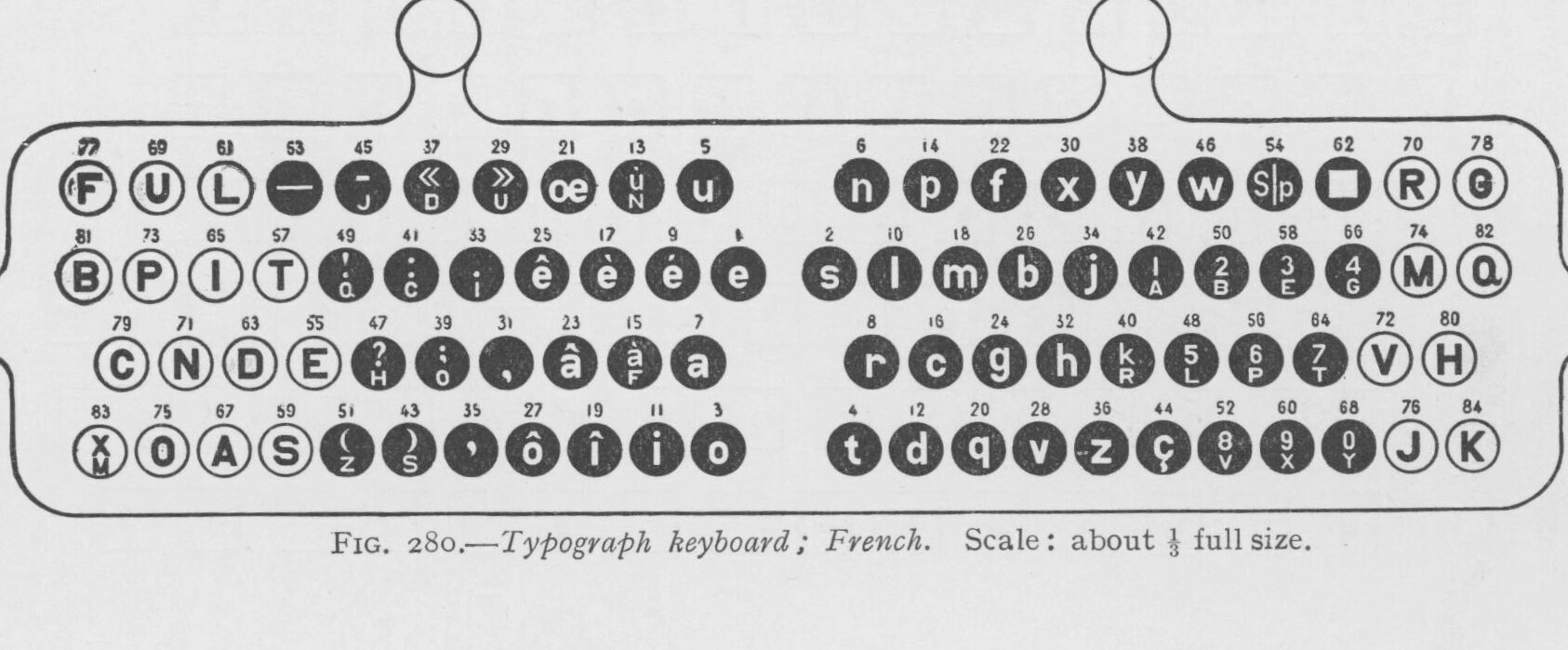

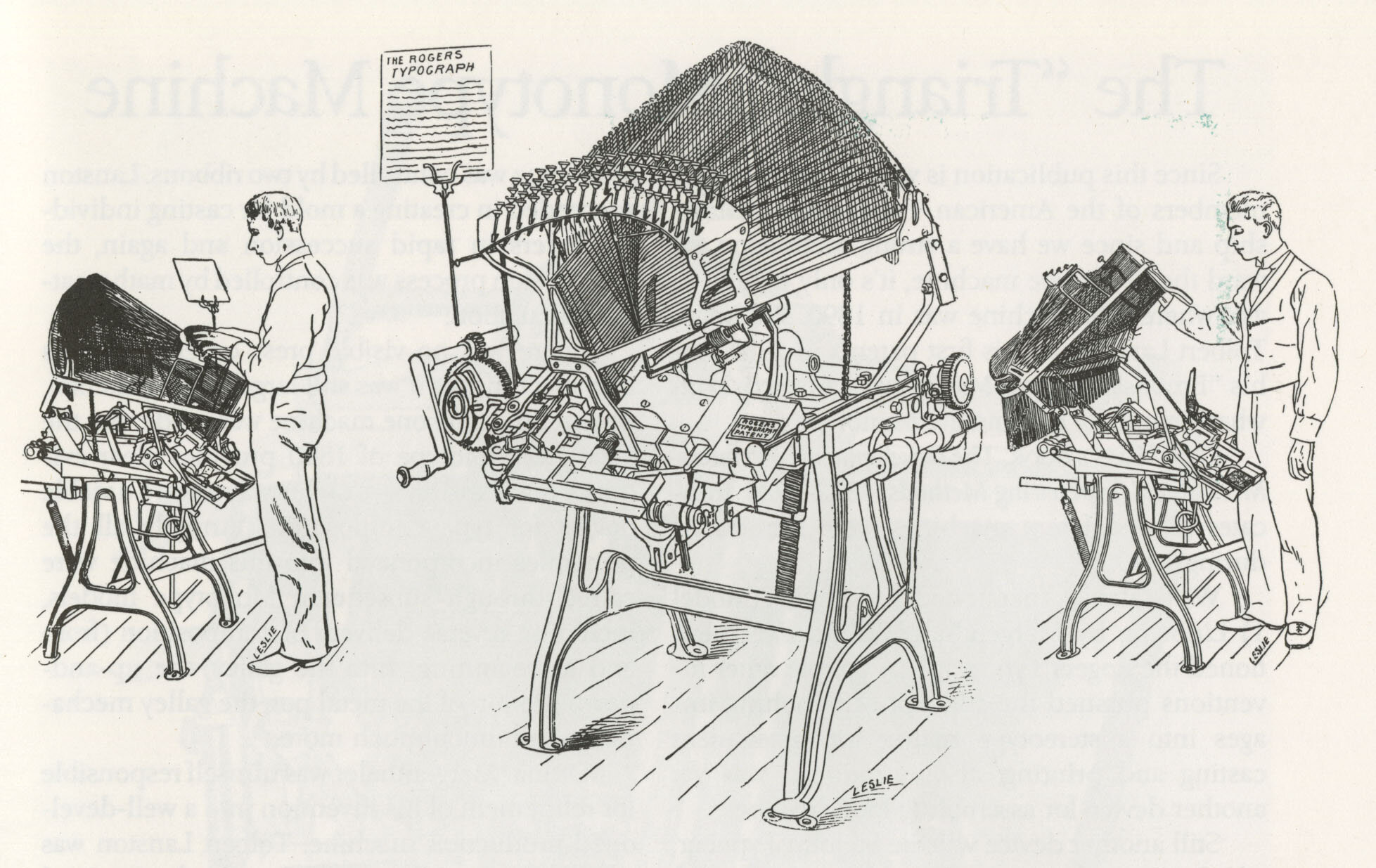

This was how Rogers’ typecasting machine worked: like the Unitype and Linotype, it was operated using a keyboard. The keyboard was connected to a series of wires with matrices hanging on the end. Each matrix has an indented mold to form a letter and multiple matrices can be gathered to form words and sentences. When the operator hit a key, a matrix slid down the wire to the center of the machine, near the keyboard. The operator then pushed a lever, and a pot of molten metal came up to fill the matrices, casting a line of type. These lines of type would be placed in a press to print a page of text and then thrown back into the pot of molten metal to be recycled for the next day. To replace the matrices after the type had been cast, the operator would take a large handle under the keyboard and lift the wires, so they tipped backwards, and the matrices slid back into place.

(If you need a visual for how this machine worked, check out our video on typesetting and typecasting below.)

The Typograph was lightweight, economical, easy to use and easy to fix. Unfortunately for Rogers, the Linotype was invented in 1886 so by the time he came with his own typecasting machine in 1890, the Linotype was already going on the market. The Typograph might have found success as the budget alternative to the Linotype, but the Linotype company wasn’t interested in entertaining any competition. Even though the Linotype and the Typograph were very different machines, Rogers was hit with patent infringement by the Linotype company. They had patented the idea of casting a bar of type, which stamped out any competition

Since there was no way to sell the Typograph in America, Rogers sold the rights to his machine overseas to German printers and publishers, where the patent was not applicable. The German Typograph Company manufactured it successfully for many years and sold it to small print shops around Europe. The Typograph was an affordable and intuitive machine. It only required one person in a shop to operate it and maintain it, which was ideal for small shops in remote areas that had limited labor. By contrast, the Linotype was quite large and expensive, and it needed an operator as well as a skilled technician to keep it running.

The Museum’s founder, Ernie Lindner, acquired the Rogers Typograph straight from the source. He traveled to Germany after WWII and visited the factory that manufactured the Typograph. The company had decided to start producing the Typograph again and they asked Ernie, who was an American equipment dealer, to represent the company and sell the machine for them. Ernie was not particularly interested in selling the new machines, but he did ask around about older models. He managed to find one Typograph in the back from the 1890s, which is now in the Museum’s collection.