LITHOGRAPHY, HELIOGRAPHY, & PHOTOGRAPHY Part Two

/LITHOGRAPHY, HELIOGRAPHY, & PHOTOGRAPHY

Part Two

Last month we learned about The Graphic Effect of the Industrial Revolution and the invention of lithography. This month we’ll see how lithography had an impact on the creation of another Industrial Revolution invention, photography.

Images from Light

Nicéphore Niépce and his brother Claude were avid inventors. In the early 19th century, the brothers constructed a prototype of an internal combustion engine. Their machine was strong enough to power a 2,000-pound boat upstream on the Saône River in eastern France. On July 20, 1807, the brothers were awarded a patent for their invention, which was signed by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

It was this love for creation and invention that moved Nicéphore Niépce to explore the newly invented art form of lithography. He soon realized he lacked the necessary skill and artistic ability to draw images onto the litho stones.

In her book, A to Z of STS Scientists, Elizabeth Oakes credits Niépce’s son, Isidore, with the creation of the artwork used on his lithographs. While his son was creating the designs, Niépce focused on the reproduction process. His goal was to invent a mechanical device that could produce images, thereby eliminating the need for lengthy artistic training.

All of the items necessary to create these images seemed to be right in front of Niépce, it was just a matter of putting them together. He was fully aware of inventions that could reproduce multiple images from a single plate. He understood lithography and was familiar with copperplate engraving. Combining this knowledge with his understanding of chemical reactions and his familiarity with the something known as the camera obscura (the earliest version of the camera), led Niépce to believe that he could create images employing light.

Painting with Light

The camera obscura, in one version or another, dates back to prehistory. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the device was quite popular among artists. It allowed individuals to place the camera box in front of an object and with the use of a small hole, lens, mirror, and ground glass they could see and trace an image of the object on to a piece of paper (see image below). Niépce’s dream was to use the camera obscura to produce an image on a litho stone, copper plate, or piece of paper.

Beaumont Newhall, in his definitive work The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present, explained that in 1816, Niépce began experimenting with paper and various chemicals to “paint” with light. Niépce was disappointed with his first attempts because they resulted in producing a negative image. He wanted to “secure pictures directly in the camera” thus he needed a positive image.

The Invention of Heliography

To create positive images, Niépce turned his attention to other materials that were affected by light. Eventually, he focused his experiments on Bitumen of Judea, naturally occurring asphalt. In an 1824 letter to his brother Claude, Niépce explained he had his first real success using bitumen applied to the surface of a lithographic stone, which was then exposed to light through a camera obscura. For the first time, he obtained a fixed image of a landscape. Though Niépce’s letter claimed he had produced the first photograph, there is no physical evidence of the event: Niépce ground out the exposed image from the stone so he could use the stone in further experiments.

Niépce also explored the use of metal plates. The next attempt to record an image from light is recorded in a letter from Niépce’s son, Isidore in 1825. Niépce covered a polished pewter plate with Bitumen of Judea. He then covered the plate with a sheet of paper already printed with an engraving of a boy and a horse; both were exposed to direct sunlight. In essence, Niépce was making a contact print.

The sunlight “exposed” the plate except for the area covered by the lines on the engraved paper. According to Isidore, after the exposure was finished, Niépce “immersed the plate in a solvent which, bit by bit, brought out the image which, until then, had remained invisible…” Niépce had created a photochemical process to record a positive image onto a plate. He called it heliography, which literally means “sun writing.”

The lines on the plate were too shallow to fill with ink and reproduce multiple copies of the image. Thus Niépce sent the plate to an engraver who worked the lines of the plate so the image could be replicated.

Examples of his process still survive today. The image on the right is a print made from one of Niépce original 1825 heliographic plates. The print is simply a sheet of plain paper printed with ink using a printing press, like ordinary etchings, engravings, or lithographs. What makes this print different is that the printing plate used was created photographically by the heliographic process rather than by hand engraving or drawing on lithographic stones. The print can be found in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. (https://pdfs.fr/)

The Invention of Photography

These “sun writings” were more photo-engravings than a photograph. Not satisfied, Niépce began experimenting with glass, copper, and polished silver plates. He even tried using lavender oil and iodine vapors that would interact with the Bitumen of Judea. His experiments led to superior quality images.

While the exposure times for the images were long, sometimes hours or days, in 1826 or 1827 Niépce finally created what is considered genuine photographs in black and white on a metal plate. The preciseness of these images was amazing for the time. Below you’ll find an image of the oldest surviving photograph formed in a camera.

The photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras, shows parts of the buildings and surrounding countryside of Niépce’s estate, Le Gras, as seen from a high window.

The Development of Photography

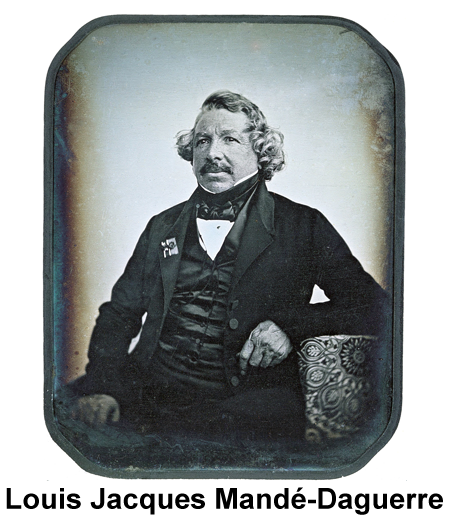

While Niépce was improving his invention, not far away, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre was also experimenting with the camera obscura. Except Daguerre was using phosphorescent powders to record an image. Unfortunately, these images were only visible for a few hours, and then they slowly faded away. According to Newhall, both inventors shared a mutual lens maker, Chevalier of Paris. Through this mutual acquaintance, the two began exchanging correspondence.

At first, both men were cautious, not wanting to reveal too much to the other regarding their experiments. Then the two met in September of 1827. Niépce wrote to his son Isidore to tell him about the meeting.

“I have had many and very long interviews with M. Daguerre,” wrote Niépce. “He came to see us yesterday. His visit lasted for three hours…and the conversation on the subject which interest us is really endless….”

After three years of correspondence and meetings, the two men finally joined forces and became business partners in December of 1829. Unfortunately, four years into their partnership, Niépce suffered a stroke and died; Isidore took his father’s place in the business.

Over the following years, Isidore Niépce and Louis Daguerre improved on the photographic process. Their modifications eventually led to the development of what they termed “daguerreotype.”

Photography Evolves

Nicéphore Niépce’s understanding of lithography led to his development of heliography. By trial and error, he was able to improve his technique, and his partnership with Daguerre advanced the process yet further. After he was gone, photography continued to evolve.

Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot used paper as an intermediate negative to produce the first negative-positive process in 1841. This modification made it possible to make multiple copies of the same image.

For decades, photographers continued to use glass, metal, and paper as the base for their images. It was the American George Eastman who had the idea to replace those traditional base materials with celluloid rolls, and the concept of film rolls was born in 1888.

It’s noteworthy how one invention often inspires the creation of another. The evolution and stories of lithography and photography are only two innovations that had a profound effect on the printing industry. Whether through serendipity, trial and error, or evolution, the development of technology during the Industrial Revolution was a testament to man’s inventive drive and creative abilities.

At The International Printing Museum in Carson, California, visitors can explore these inventive stories and so much more. Every year 25,000 students are exposed to the collection through working and engaging tours. Just maybe some of them will be inspired to create and invent their own solutions to the problems of the future.