WOMEN IN PRINTING HISTORY PART 2:Women Printers in the American Colonies

/WOMEN IN PRINTING HISTORY PART 2:

Women Printers in the American Colonies

The Great Puritan Migration

In 1638, as Puritans continued to leave England for the new world, one particular immigrant had an idea different from all the rest. Reverend Jose Glover had a plan to bring a printing press to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He secured passage on the ship John of London for himself, his wife and five children, servants, and household furnishings. He also brought a printing press, 240 reams of paper, and a case of assorted type.

Unfortunately, Reverend Glover never lived to see his dream of setting up a print shop in the new world fulfilled. During the voyage from England, Glover contracted a fatal illness, probably smallpox, and died.

Once the ship arrived at the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Reverend Glover’s wife, Elizabeth, took matters into her own hands and went to work on setting up shop. Mrs. Glover purchased a house for Stephen Day, an indentured locksmith, who was under financial contract to her husband. The press was placed in one of the rooms of this house. Most historians believe that it was in this house, in 1639, that Stephen Day and his son Matthew printed The Freeman’s Oath broadsheet.

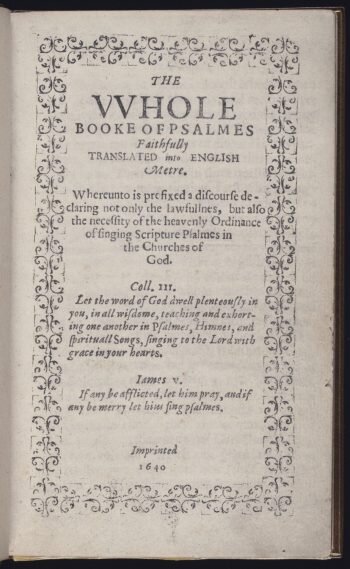

In 1640, after the printing of The Freeman’s Oath and an almanac, Stephen and Matthew began work on the first book published in the American colonies, The Whole Booke of Psalmes.

On June 21, 1641, Elizabeth married Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard. For the next two years, Elizabeth maintained control of the press. It wasn’t until her death in 1643 that her land and property, including the printing press, was passed on to Dunster and subsequently to Harvard College. During the same year, Matthew Daye replaced his father as the official operator of the press after the elder Daye was briefly jailed for fraud.

On November 26, 2013, a copy of The Bay Psalm Book sold for almost 14.2 million dollars, the most costly book in the world at the time.

The Franklin Legacy

Women printers also figured prominently during the American Revolution, due in some part to the help of Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin.

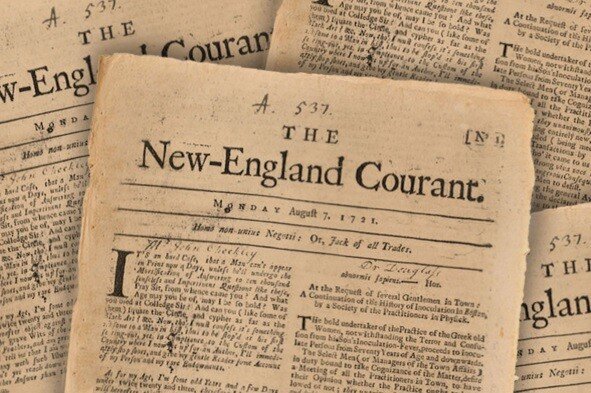

As a young boy of 12, Franklin was indentured to his older brother James. Beginning in 1721, James, his wife, Ann, and brother, Benjamin, worked together to publish the first independent American newspaper, the New-England Courant. That early print training benefited both Benjamin and Ann later in life.

In 1731, Benjamin Franklin took his training and experience in the printing industry and turned it into a franchise. Franklin helped his best employees, and others interested in the industry, start their own printing business. He would buy the equipment and pay the rent on the shop for six years. At the end of six years, his partners had the option to buy Franklin out and run the business on their own or maintain the partnership. By the time he retired as America’s first millionaire, Franklin’s printing empire had reached from New England to the Caribbean.

In 1734 Franklin entered into a business agreement with Lewis Timothy. Later, when discussing Lewis’ business sense, Franklin wrote, “He was a man of learning, and honest but ignorant in matters of account; and, tho’ he sometimes made me remittances, I could get no account from him, nor any satisfactory state of our partnership while he lived.”

Five years into their six-year agreement, on January 4, 1739, the South-Carolina Gazette noted that Lewis Timothy had died due to “an unhappy accident.” Following the death of her husband, Elizabeth Timothy became the first woman publisher of a newspaper in America. For seven years, she published the South Carolina Gazette in Charleston, in partnership with Franklin. And, in essence, became the first female franchisee.

While Franklin was not impressed with Lewis Timothy’s business sense, he felt the opposite of Elizabeth’s ability to run a print shop. “Her accounts were clearer, she collected on more bills, and she cut off advertisements if payments were not current,” said Franklin.

Franklin even mentioned Elizabeth in his autobiography. He said Elizabeth operated the Gazette with “regularity and exactitude… and managed the business with such success that she not only brought up reputably a family of children but at the expiration of her term was able to purchase of me the printing house and establish her son to it.”

Benjamin Franklin’s early training led to his business success. In much the same way, his sister-in-law, Ann Franklin’s printing experience, provided her with a solid business background that would serve her well. At the same time, it brought Benjamin Franklin full circle, back to his printing roots.

James and Ann Franklin

In 1727 James and Ann Franklin moved to Newport, Rhode Island, and opened the colony’s first print shop. By 1732 the couple started the Rhode-Island Gazette. James was the editor, and Ann worked as an assistant printer. Ann knew how to both set type and operate the press. According to Dorothy A. Mays, in her book, Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World, “Ann was an active participant in her husband’s print shop.”

In 1735 James became ill, and his brother Benjamin came to Newport for a visit. Benjamin promised James, who was on his deathbed, he would bring up his six-year-old son, James Jr., in the printing industry. After James succumbed to his illness on February 4, 1735, Ann’s extensive printing and business experience allowed her to take over the business. Soon thereafter, James Jr. or Jemmy, as he was called, went to Philadelphia with his uncle.

Within a year of her husband’s death, Ann secured the lucrative position of the official printer for the Rhode Island assembly. In her post, she printed the colony’s charter granted by Charles II of England. She also printed sermons for ministers, advertisements for merchants, as well as popular British novels.

While Ann Franklin ran the printing business in Newport, Jemmy studied with a private tutor along with his cousin in Philadelphia. In 1740, at the age of 10, he signed his Indenture papers and became apprenticed to his uncle Benjamin.

Ann Smith Franklin, now a master craftsman, trained her two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, as typesetters and shopkeepers. After serving his apprenticeship, Jemmy returned to Newport, and in 1748 he became a partner in his mother’s printing business. Their company continued to produce books, almanacs, pamphlets, and legal announcements.

Look closely at the Acts and Laws image and you’ll see “Printed by the Widow Franklin…”

Ann Smith Franklin died in 1763 and was buried in the Newport Common Burying Ground and Island Cemetery.