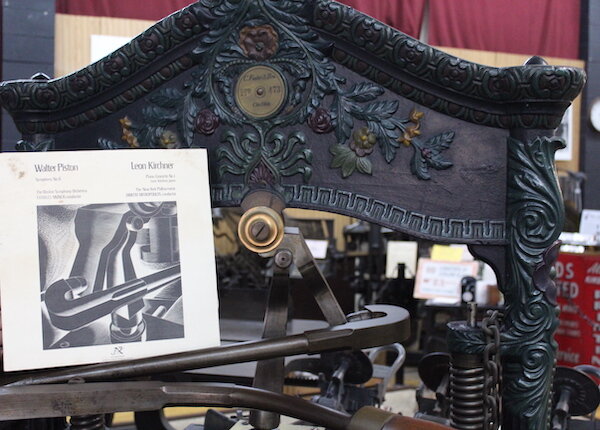

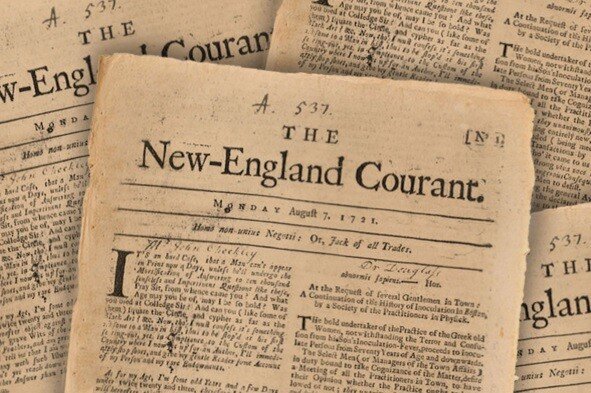

As a young boy of 12, Franklin was indentured to his older brother James. Beginning in 1721, James, his wife, Ann, and brother, Benjamin, worked together to publish the first independent American newspaper, the New-England Courant. That early print training benefited both Benjamin and Ann later in life.

In 1731, Benjamin Franklin took his training and experience in the printing industry and turned it into a franchise. Franklin helped his best employees, and others interested in the industry, start their own printing business. He would buy the equipment and pay the rent on the shop for six years. At the end of six years, his partners had the option to buy Franklin out and run the business on their own or maintain the partnership. By the time he retired as America’s first millionaire, Franklin’s printing empire had reached from New England to the Caribbean.

In 1734 Franklin entered into a business agreement with Lewis Timothy. Later, when discussing Lewis’ business sense, Franklin wrote, “He was a man of learning, and honest but ignorant in matters of account; and, tho’ he sometimes made me remittances, I could get no account from him, nor any satisfactory state of our partnership while he lived.”

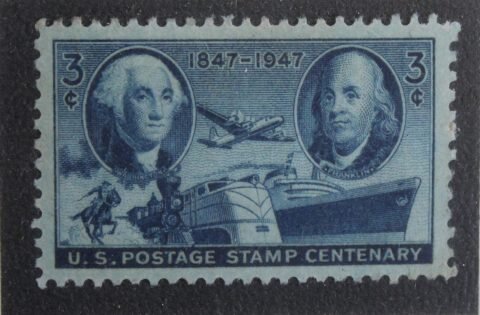

Five years into their six-year agreement, on January 4, 1739, the South-Carolina Gazette noted that Lewis Timothy had died due to “an unhappy accident.” Following the death of her husband, Elizabeth Timothy became the first woman publisher of a newspaper in America. For seven years, she published the South Carolina Gazette in Charleston, in partnership with Franklin. And, in essence, became the first female franchisee.

While Franklin was not impressed with Lewis Timothy’s business sense, he felt the opposite of Elizabeth’s ability to run a print shop. “Her accounts were clearer, she collected on more bills, and she cut off advertisements if payments were not current,” said Franklin.

Franklin even mentioned Elizabeth in his autobiography. He said Elizabeth operated the Gazette with “regularity and exactitude… and managed the business with such success that she not only brought up reputably a family of children but at the expiration of her term was able to purchase of me the printing house and establish her son to it.”

Benjamin Franklin’s early training led to his business success. In much the same way, his sister-in-law, Ann Franklin’s printing experience, provided her with a solid business background that would serve her well. At the same time, it brought Benjamin Franklin full circle, back to his printing roots.

James and Ann Franklin

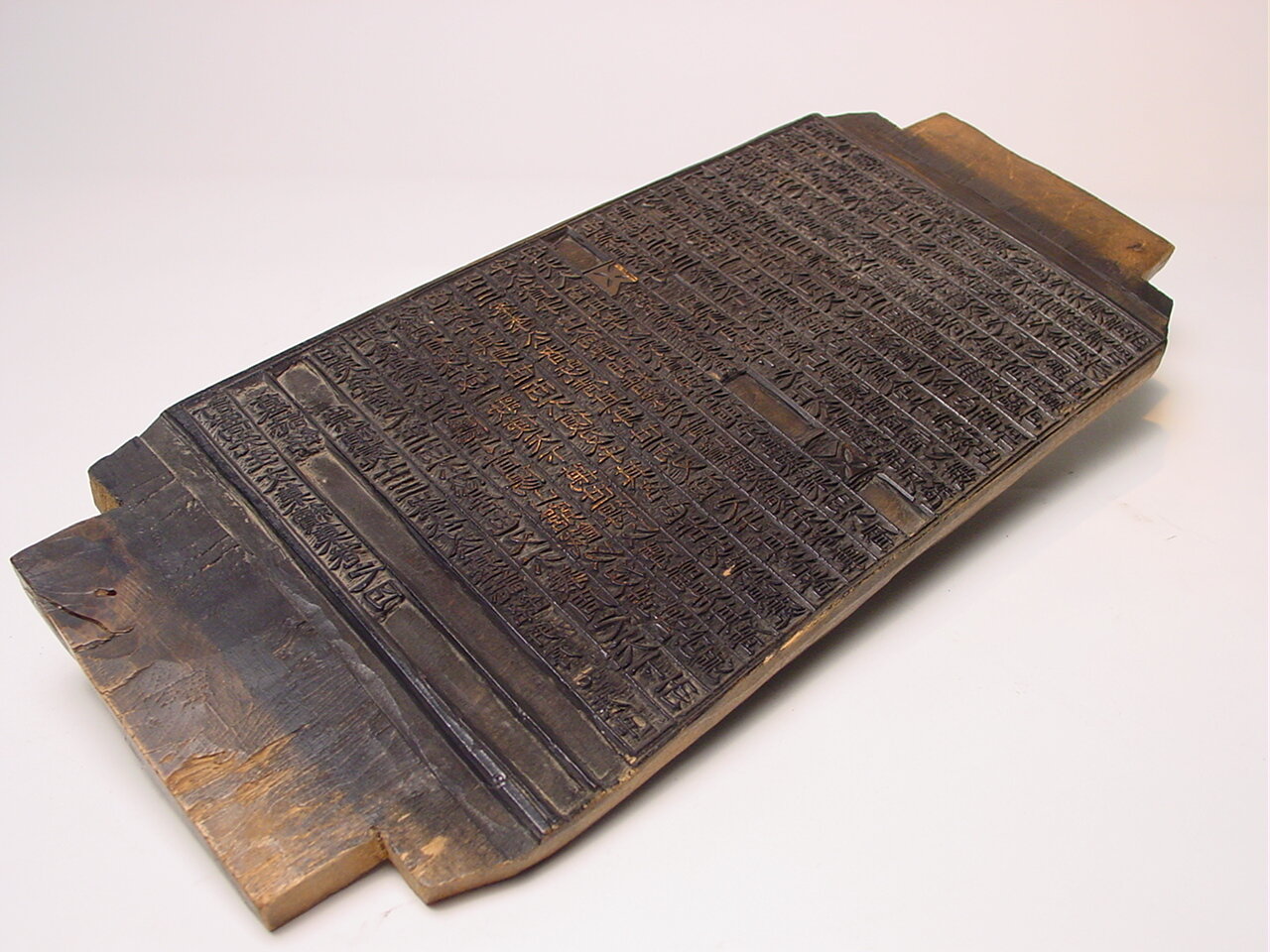

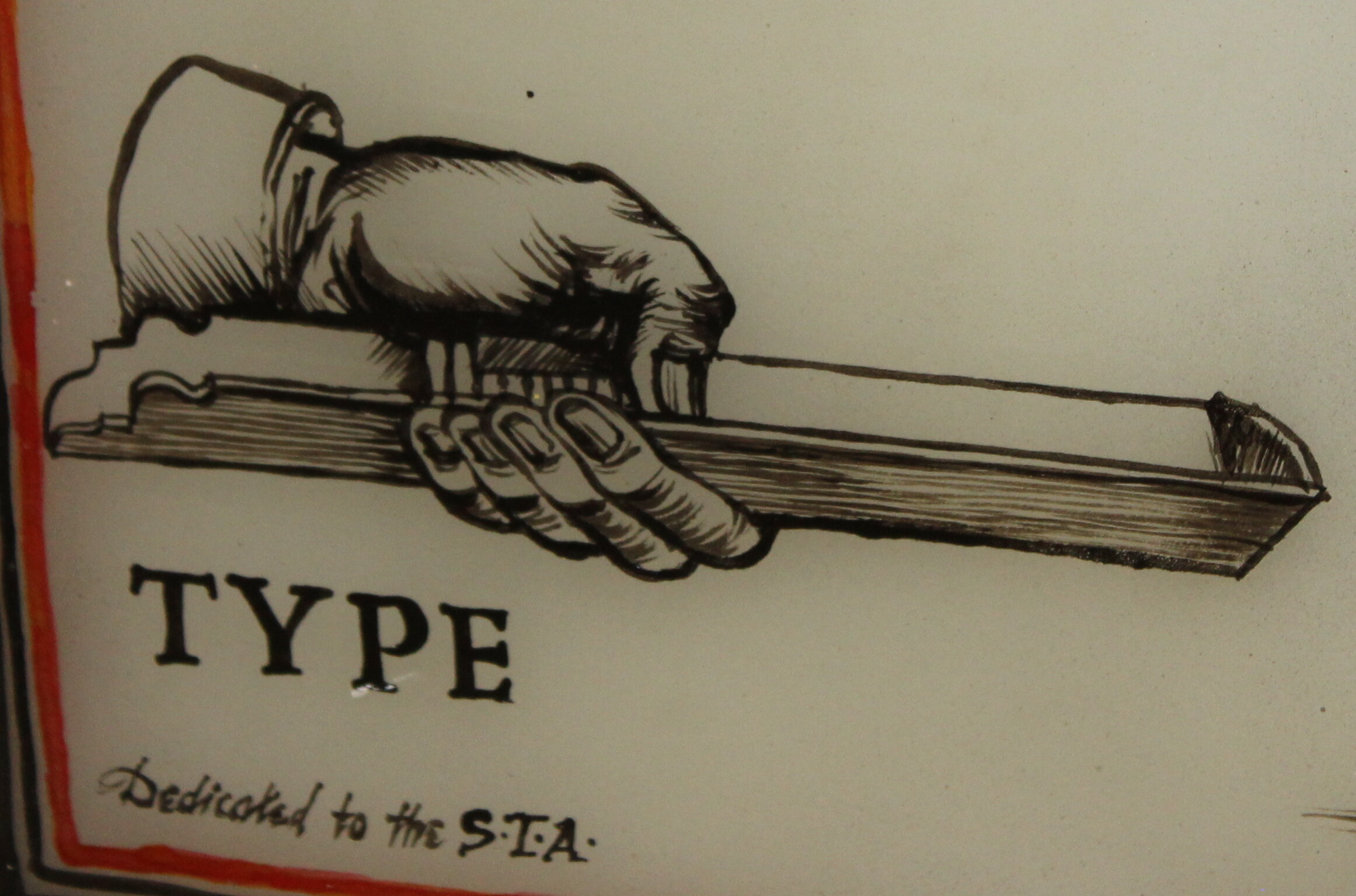

In 1727 James and Ann Franklin moved to Newport, Rhode Island, and opened the colony’s first print shop. By 1732 the couple started the Rhode-Island Gazette. James was the editor, and Ann worked as an assistant printer. Ann knew how to both set type and operate the press. According to Dorothy A. Mays, in her book, Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World, “Ann was an active participant in her husband’s print shop.”

In 1735 James became ill, and his brother Benjamin came to Newport for a visit. Benjamin promised James, who was on his deathbed, he would bring up his six-year-old son, James Jr., in the printing industry. After James succumbed to his illness on February 4, 1735, Ann’s extensive printing and business experience allowed her to take over the business. Soon thereafter, James Jr. or Jemmy, as he was called, went to Philadelphia with his uncle.