WOMEN IN PRINTING PART 3:Women Printers in the 19th Century

/WOMEN IN PRINTING PART 3:

Women Printers in the 19th Century

The Industrial Revolution

New technologies had an enormously positive impact on the printing industry during the Industrial Revolution. This was the time of Lord Stanhope and his cast-iron press. In Europe, the flatbed printing press was replaced with the cylinder press thanks to Koenig and Bauer. And in America, Richard M. Hoe’s steam-powered rotary printing press allowed the printing of millions of copies of a page in a single day. It was during this time that Lydia Bailey took over her husband’s printing business, and its many debts, to support herself and her four children.

Lydia was no stranger to the printing industry. Her father came from a dynasty of printers and papermakers. Her uncles on her father’s side operated a busy paper mill outside of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Her uncles on her mother’s side, Jacob and Francis Bailey, were successful revolutionary-era printers. In addition to printing the first edition of the Articles of Confederation and copies of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Francis Bailey acted as printer for Congress and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. With a background like this, Lydia was the perfect person to take over a failing printing business.

Lydia’s husband, Robert, was a terrible businessman. He made it a practice to extend credit. And, as any printer knows, this can only lead to disaster. When he died in 1808, Lydia found herself the owner of a floundering printing business. But, due to her keen business sense, within four years of Robert’s death, Lydia was winning praise from her contemporaries. She was doing so well that in 1813 Bailey obtained the contract to become Philadelphia’s official city printer, a post she mostly held until the mid-1850s.

Lydia Bailey not only ran the business, she learned to set type. She also claimed to have instructed “forty-two young men, including some of the city’s future master printers, in the typographic arts.”

Bailey’s shop, at its peak, was one of the largest in the city, employing more than forty workers. This was due in large part to her decision to change the focus of the company from being both a publisher and printer to focus strictly on job printing. While the shop continued to print some small publications, her primary work consisted of contract job printing, including blank forms, cards, receipts, handbills, legal documents, bills of lading, and the like. Much of this steady work came from contracts she acquired for job printing with the University of Pennsylvania and various banks and canal companies.

Lydia Bailey’s career spanned more than half a century. In 1869 she died in Philadelphia at the age of ninety.

Women Printers in the United Kingdom

In 1860 a group of women involved in the British suffrage movement, led by women’s rights activist Emily Faithfull, founded Victoria Press in London, England. Faithfull advocated for women’s rights. She fought so women could have the opportunity to work at well-paying jobs the same as men. Faithfull’s goal with Victoria Press was not just to print pamphlets and publications that promoted the movement, but to have those materials produced by women.

The most notable book issued by the press was The Victoria Regia: A Volume of Original Contributions in Poetry and Prose. Edited by Adelaide A. Proctor, in 1861. The book highlighted the poems and writings of women while also demonstrating the typesetting prowess of the female compositors.

Faithfull’s printing operation caught the attention of Queen Victoria, and in 1861 Faithfull was appointed by royal warrant ‘Printer and Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty.’

In 1863, Faithfull began publishing The Victoria Magazine. Through this magazine, she continued to advocate for a women’s right to fair and equal employment opportunities.

In 1867 Faithfull turned over management of the press to William Wilfred Head, a partner in the press. Head bought Faithfull out in 1869.

After her success with The Victoria Press, Faithfull, along with English feminist and trade unionist Emma Paterson, went on to establish the Women’s Printing Society, in 1878.

The company published feminist tracts while providing employment opportunities for women. According to James Ramsay MacDonald in his book, Women in the Printing Trades: A Sociological Study, “the Women’s Printing Society was set up to allow women to learn the trade of printing, and provided an apprenticeship program.” By 1899, the company employed 22 women as compositors. Women also worked as proofreaders, bookkeepers, and managers.

Women Printers in San Francisco

During this same time, San Francisco was becoming a printing and publishing hub. According to Libby Ingalls in her Historical Essay, Women in Printing, “In the 1860s, typesetting was the most prestigious job for women in San Francisco. The job required skill in spelling and grammar, along with manual dexterity, so typesetters tended to be better-educated and fast learners. But opportunities were extremely limited. The strong prejudice against women in the workplace locked them out of higher-paid jobs.”

Due to the California gold rush in 1849, the need for printed materials exploded. Newspapers, legal documents, broadsides, and the like were needed to run businesses and the state and local governments. The work was there, but according to Ingalls, “Men did not want to work side by side with women, unions banned them, their salaries were lower, and they were not permitted apprenticeships or technical training.”

After years of fighting for their rights, women finally had a champion to help voice their opinion. In 1858 Mrs. A.M. Schultz and her assistant, Mrs. Hermione Day began publishing a new woman’s literary magazine, The Hesperian. The magazine took on labor issues related to women, including employment inequality, lack of opportunity, and lower wages for women.

Within two years, Day took over the business and expanded beyond magazine publishing to job, book, and fancy printing. Along the way, she hired women to work for her company.

Women’s Co-operative Printing Union

In 1868, Mrs. Agnes B. Peterson and other trained female typesetters came from back east to California. While trying to find work to support herself and her child, Peterson ran into some difficulties. According to The Ladies’ Repository, Volumes 39-40, Peterson found that the owners of the print shops were “quite willing to give me employment, but the Typographical Union refused to permit me to work….”

The problem hinged on the fact that the women typesetters refused to work for less than the Union rates for men. The Union exercised power over most of the printers in San Francisco, so these companies denied work to the women “even in instances where they needed more help than they could obtain from the ranks of good male compositors.”

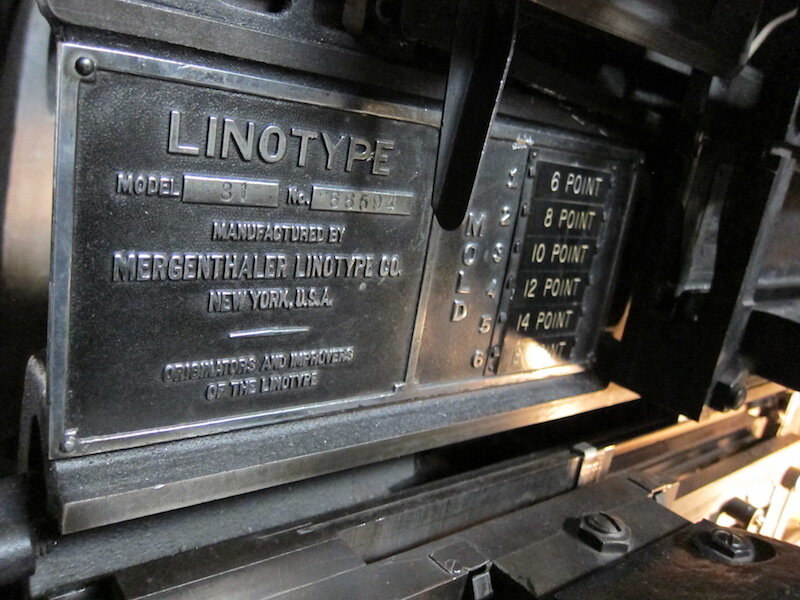

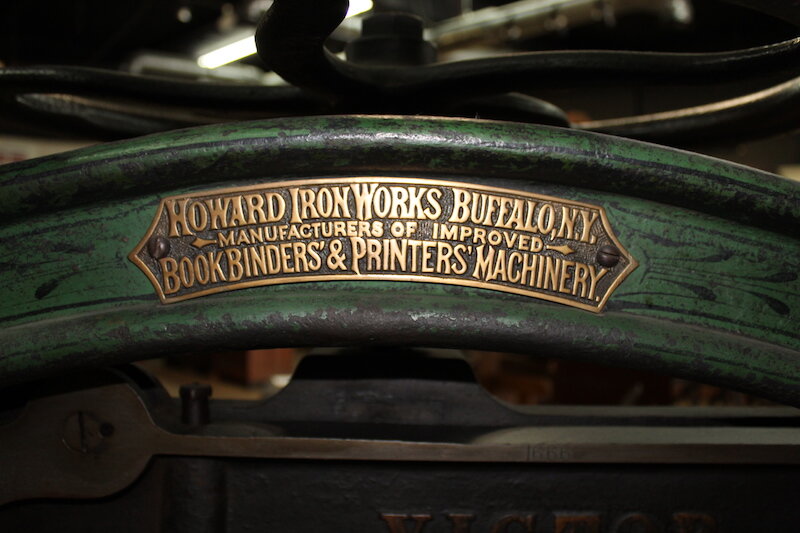

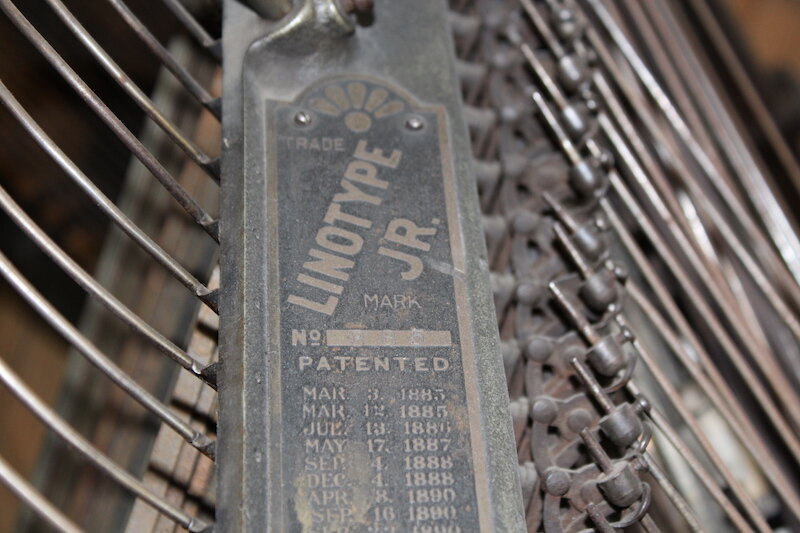

Peterson and her female typesetting companions fought back against the Union. With the help of Wells Fargo Bank, the women obtained financing and, in 1869, co-signed incorporation documents to create the Women’s Co-operative Printing Union (WCPU).

The women rented space, bought presses and cases of type, and started to work. One of their first clients was Wells Fargo. The WCPU printing checks for the bank.

According to Ingalls, during the next 18 years, “the WCPU printed every variety of book, including fiction, nonfiction, children’s books, and cookbooks, along with Spiritualist and feminist journals.”

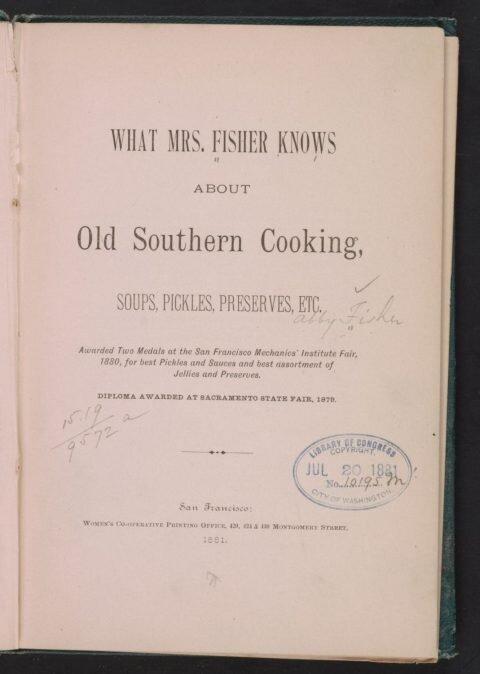

One book of particular note is believed to be the first cookbook by an African American. The book, by Mrs. Abby Fisher, was entitled What Mrs. Fisher knows about old southern cooking, soups, pickles, preserves, etc.

Fisher was a fantastic cook. In 1877, soon after she, her husband and 11 children migrated from Mobile, Alabama to San Francisco, California, she put her talents to work. Fisher opened Mrs. Abby Fisher & Co., a pickle and preserves manufacturing business.

In 1879 Fisher entered her tasty preserves in the Sacramento State Fair and won big. In 1880, she won a bronze medal for the best pickles and sauces, and a silver medal for the best assortment of jellies and preserves at the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Fair. The jurors later wrote that “her pickles and sauces have a piquancy and flavor seldom equaled, and, when once tasted, not soon forgotten.”

With a flourishing company and awards and ribbons to confirm her culinary abilities, a book deal was a logical next step.

In the preface of her book, Fisher suggests that friends and patrons alike encouraged her to keep a written record of her recipes. This, though, presented a problem. Fisher was an ex-slave who could neither read nor write.

Abby Fisher had all of her recipes in her head. Now she needed to get those into print. When you think of the obstacles faced by Agnes Peterson and the other female typesetters who started the WCPU, you can understand why this cookbook would be the perfect project. As Tricia Martineau Wagner wrote in her book African American Women of the Old West, “These women would have been very sympathetic to assisting a female in getting her cookbook published.”

Fisher’s recipes would first have to be transcribed before they could be typeset and printed. But the women of the WCPU would happily do so “in order to preserve some of the best southern cooking of their day.”

The International Typographical Union

In 1876 the International Typographical Union (ITU) revised its rules, giving the local organizations full discretion in the admission of women. According to Ingalls, “San Francisco Local #21 still refused.” It wasn’t until 1883 that the ITU opened membership to women in all Locals. Once admitted, women received the same pay and protection as their male counterparts.

The 19th century was a difficult time for women in the printing industry. They faced opposition but also fought and won against the forces that tried to keep them down.

Next week we will cover a female printer of the 20th century. Our fourth and final installment of Women in Printing History may surprise you.

To learn more about the #GirlsWhoPrint and #PrintHerStoryMonth initiative visit GirlsWhoPrint.net